If you don’t want to read the post and just want to mess around with the spreadsheet, here it is.

For a lot of people, it seems that the decision of whether or not to have children is black-and-white. Some grow up knowing that their lives will feel empty and meaningless without children, while others staunchly insist that they will never have one.

I was in the third camp. Oh, sure, as an adolescent and young(er) adult I was very comfortable proclaiming one stance or another without giving them much thought, but it wasn’t until more recently that I decided to really sit down and examine the pros and cons of having children.

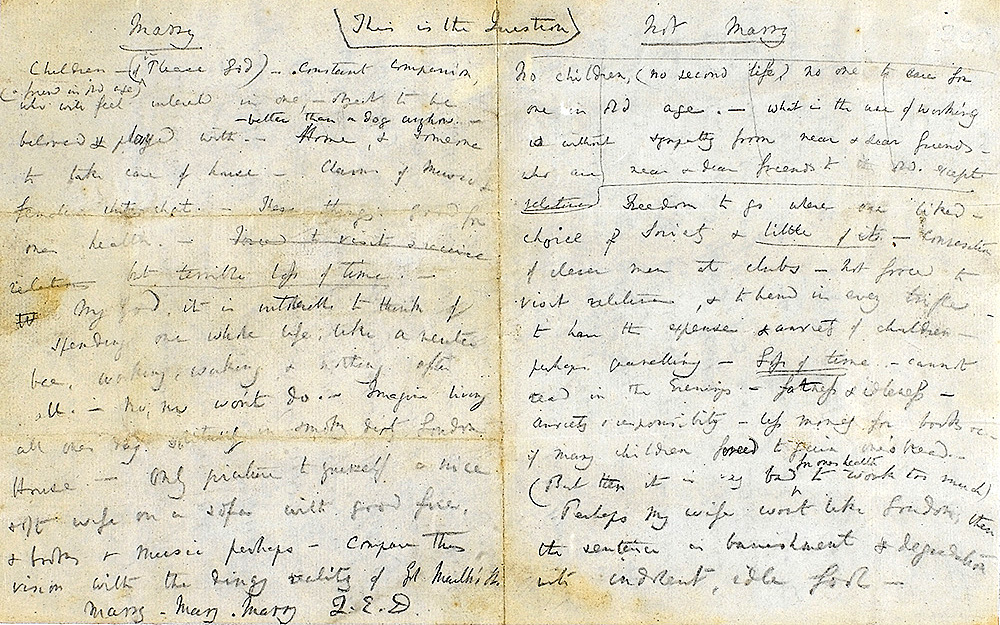

Charles Darwin’s decision on whether or not to marry. 1

Charles Darwin’s decision on whether or not to marry. 1

Sadly, my cost-benefit analysis was not as easy as Darwin’s. After everything was down on the page, it still didn’t seem clear which one would be the better choice in the long term, largely because it was nearly impossible to quantify the costs and the benefits. How do you weigh “freedom to go where I want” against “satisfaction from watching someone you love grow and change,” for example? So, I decided to do as any good mathematically-inclined person would: get as many numbers as I can.

A word of warning: if the idea of associating a monetary value with a child is disturbing to you, it would be a good idea now to close this tab.

I. The numbers

The easiest thing to put a number on is the cost of raising a child. According to this article on Moneysense, in 2015, it would have costed roughly $254k to raise a child from birth to age 18 in Canada, or $13,366 per year. After that, there is university. Moneysense does not offer a figure for how much the average university student costs their parents, but I ballparked it at $20000 – roughly equal to the previous cost per year, plus a year’s worth of tuition at UBC. This yielded a preliminary total of $334k (CAD).

But I was not satisfied with this number. For one thing, it does not take into account one of the biggest downsides of having children for middle class, professional women: the harm it does to one’s career. As well, it neglects the power of compound interest and therefore the lost investment opportunity cost. After all, the prime childbearing years for a woman (20-30) are also the prime retirement saving years. A dollar invested at age 25 is worth $3.87 invested at age 45. 2

This article from the Wall Street Journal offers a more realistic-sounding figure of $1.1M. But I wasn’t satisfied with that number, either, largely because two of the factors they mention – the insane cost of American private universities, and taking many years off from work to raise a child – are unlikely to apply to me. And the WSJ article still doesn’t mention opportunity cost.

I dug up more numbers:

- Employment insurance pays out 55% of a new (birth) mother’s previous income for up to a year, but there is a cap for $537 per week. In practice, the wage penalty a woman can expect to receive in her first year after having a child must vary by an enormous amount since different women take different lengths of leave, and lower income women receive proportionally greater benefits.

- The median income for Vancouver-area women, aged 25-54, who were working full time, was $54,425 as of the 2012 census, according to StatsCan.

- The average salary increase in BC in 2016 was projected to be 2.3%, but this is a little lower than normal, so I used 2.5%; meanwhile, inflation is 2%.

- The average maternal age for a first-time birth mother in BC is 30-34 – I used 32 – while the fertility rate hovers around 1.4-1.5, which I rounded down to 1.

- Estimates of the “motherhood penalty” vary. According to this paper, it averages 5% lower per child (not sure if that’s additive or multiplicative; additive would be more punishing). This StatsCan analysis from 2009 gives 9%, 12%, and 20%, respectively, for women with 1, 2, and 3 children. I went with a 7% per child multiplicative estimate.

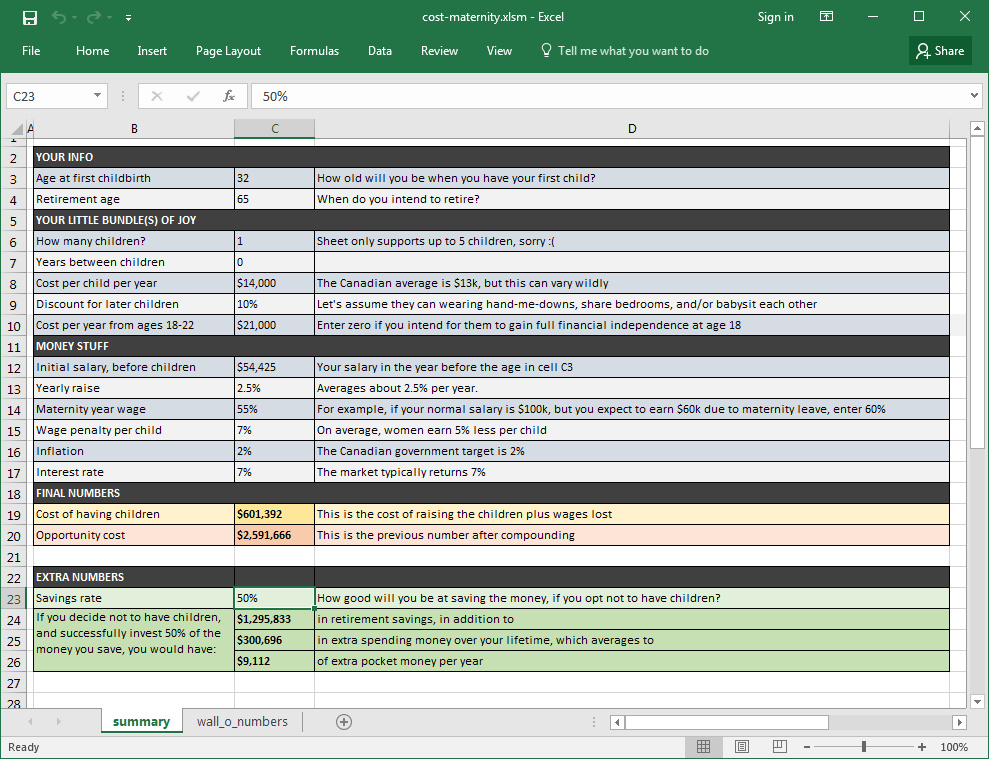

… and put them into a spreadsheet, which you can find here (clicking the link will begin the download. Also, you will need to enable macros to use the spreadsheet with your own numbers).

II. Explanation of spreadsheet

I used the values mentioned above and rounded the cost of raising a child up to $14k per year, because Vancouver is expensive.

Cost of a university-aged child was set to $21k, allowing for $7000 per year for tuition. The sheet automatically adjusts these

numbers to account for inflation.

I used the values mentioned above and rounded the cost of raising a child up to $14k per year, because Vancouver is expensive.

Cost of a university-aged child was set to $21k, allowing for $7000 per year for tuition. The sheet automatically adjusts these

numbers to account for inflation.

Additionally, I added a field for savings interest rate. The default value is 7%, as that is the historical market average. And I added the option of a discount for later children.

I used a simplified tax calculation with only 4 tax brackets. 3

Two numbers are returned near the bottom of the sheet:

- Cost of children: This is the amount each child costed to raise, plus lost wages. It does not consider interest.

- Opportunity cost: To explain, if there are two identical woman existing in parallel universes, and one of them had children and the other didn’t and instead invest 100% of the extra money she has, this is how much more woman 2 would have when they both retire.

Finally, I added an extra option to see how varying savings rates affect things.

III. The true cost, or, “An ode to compound interest”

Warning: this is the part where I will really be talking about children as if they were purchasable objects.

A few things jumped out at me while playing around with the spreadsheet.

Scenario 1: First, holy hell, children are expensive. Using the average numbers listed above, a 32-year-old Vancouver woman who gives birth in 2016 will pay $601,392 in childcare costs and lost wages throughout her lifetime. If she did not have a child and invested all of her money in an index fund, she would retire with an extra $2.59M.

Scenario 2: I tried putting in a more favourable, but still realistic scenario – maternal age of 40 with an initial income of $30,000, an optimistic 2% motherhood penalty, and earning 80% of normal wage during the maternity year. This results in an opportunity cost for the first child of $1.21M at age 65.

Scenario 3: Then I changed one variable – I reduced the maternal age from 40 to 25. The retirement savings almost triples as a result. So, if you are 25 in 2016 and considering having a child, you have a third choice other than have-the-joys-and-tribulations-of-childraising or $3.36M-extra-retirement-savings: you could wait 15 years and get a steep discount.

The takeaway: “peak childbearing age” aside, it really is better to have children as late as possible. Biology sucks.

Scenario 4: Finally, I put my mother’s statistics into the spreadsheet: first child at age 27, second child 13 years later. I have no idea what her salary was or what it would be in modern figures, so I used a reasonable sounding guess of $40000, gave her a maternity pay of 70%, and the average 7%-per-child motherhood penalty. I found out that if my mother were having us today, my sister and I would cost $1.21M, compounding to just over $5M when our mother turns 65. Just the first child (me) carries an opportunity cost of $3.41M of that $5M.

Sorry for being a brat when I was a kid, mom. Maybe it was worth watching me grow and change?

On the bright side, I now know what I’m worth – $3.41M! Hey, that’s not bad.

IV. Limitations

If these numbers seem great, consider also that it would take a superhuman amount of self discipline to force yourself to save all the money. Let’s say you’re the average Vancouver woman (scenario 1). You decide not to having children, but are not good at saving and only manage to invest 10% of the extra money. You end up with $259k of retirement savings, and get to spend an average of $16,402 per year on travel, a nicer apartment, bigger TV, etc. This scenario makes having a child seem pretty attractive – $259k is not that much for a retirement account, and as for the $16,402, I think most parents would probably agree that they get more happiness from their children than they would from taking a few extra vacations and having a bigger TV.

Also keep in mind that, with inflation, $259k or $2.59M or whatever will have less spending power in the future than it does today.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of some of the things this spreadsheet does not account for:

- Supporting a child beyond the age of 22

- The possible existence of a “fatherhood bonus” (the opposite of the “motherhood penalty”) that some social scientists have posited. In traditional heterosexual partnerships, this may offset some of the cost

- Taking additional time off after having children, or working part time

- The still-impossible-to-quantify value of “freedom to travel” or “satisfaction from watching them grow”

- Myriad other individual factors

- Starting a reality TV show and turning your children into financial assets

A final word: I have intentionally not commented on the fairness, or lack thereof, of the motherhood penalty, nor have I commented on the assumption that the female partner (in a heterosexual partnership) must always be the primary caregiver. My spreadsheet merely makes calculations based on the way things are today. The motherhood penalty and female-primary-caregiver assumption are very, very well explored elsewhere, by people much more qualified than I am to make commentary on them.

V. Final thoughts

I may as well stop dancing around the conclusion now: I am not having children, and the cost is definitely a factor.

I wonder how many other women – or couples – have also made the same choice. Judging by the dismally low birth rates in BC, probably a few, and then a few more after that who stopped after the first child even though they may have wanted more.

And I wonder what all of this means for a country whose population is increasingly ageing. If we want to reach population replacement rate4, then something must be done to encourage people to choose children and preferably to choose children early. Reducing their price tag probably wouldn’t hurt.

-

Darwin’s marriage pro-con list is hilarious (to a modern reader) and well worth a gander. Here’s an article that includes a readable transcript of his list. ↩

-

You can always calculate the expected value of any investment with \(\text{initial investment} \times (\text{annual increase} + 1)^{\text{years}}\)

So, $1 invested at age 25 with a 7% annual increase will, at age 45, be $3.87. ↩ -

Tax brackets used were:

< $20k: 0%

$20k-50k: 20%

$50k-100k: 30%

$100k-150k: 40%

> $150k: 50% ↩ -

Economists say we should aim for population replacement, but environmentalists say we shouldn’t because the earth is already overpopulated…

¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ↩